Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have developed a diagnostic tool that allows them to quickly identify whether a person with respiratory disease has severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, and the severity of their infection. The test can detect the SARS virus even if only 10 virus molecules make it into the tested sample.

“It’s good to have this in our diagnostic arsenal,” says Michael J. Holtzman, MD, the Selma and Herman Seldin Professor of Medicine and professor of cell biology and physiology. “Now, if someone comes to Barnes-Jewish Hospital or St. Louis Children’s Hospital with a severe respiratory illness suggestive of SARS, within a few hours we can determine if it is in fact SARS and quantify viral levels. Very few centers can do that right now. Rapid and accurate diagnosis obviously is critical for providing optimum care for our patients and helping us contain the disease and protect our community.”

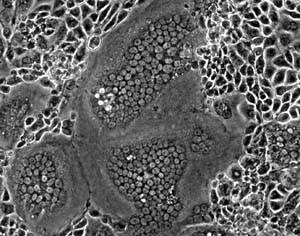

Holtzman’s team has been studying another newly identified respiratory virus called human metapneumovirus (MPV), which surfaced in the Netherlands about two years ago. For those studies, they had developed a detection system for new viruses using a technique called real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Using fragments of the viral genome as guides for “primers,” the method produces and measures the number of copies of the viral genome. It thereby allows scientists to take a small sample, for example, a nasal swab, and detect the virus even when it is present at very low levels.

With this new diagnostic method conveniently in development, Holtzman and Eugene Agapov, Ph.D., research associate in medicine, were able to quickly develop a primer for detecting the SARS virus. All they needed was the DNA sequence.

“We were especially pleased that it was easy to get not only the electronic information about the viral genome, but also a piece of the corresponding DNA from scientists working in Hong Kong,” Holtzman says. “Because these scientists were so cooperative, and because we had just been working on a similar approach to MPV, the development of this diagnostic tool went very quickly. Everything just fell into place at the right time.”

Now the team is working with Gregory A. Storch, M.D., professor of medicine, molecular microbiology and pediatrics, and director of the clinical virology laboratory at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, to use the new test in any future suspected SARS cases.